Complete Guide to Thematic Analysis: 7 Phases to Master Qualitative Analysis

📑 View contents

By Paulina Contreras

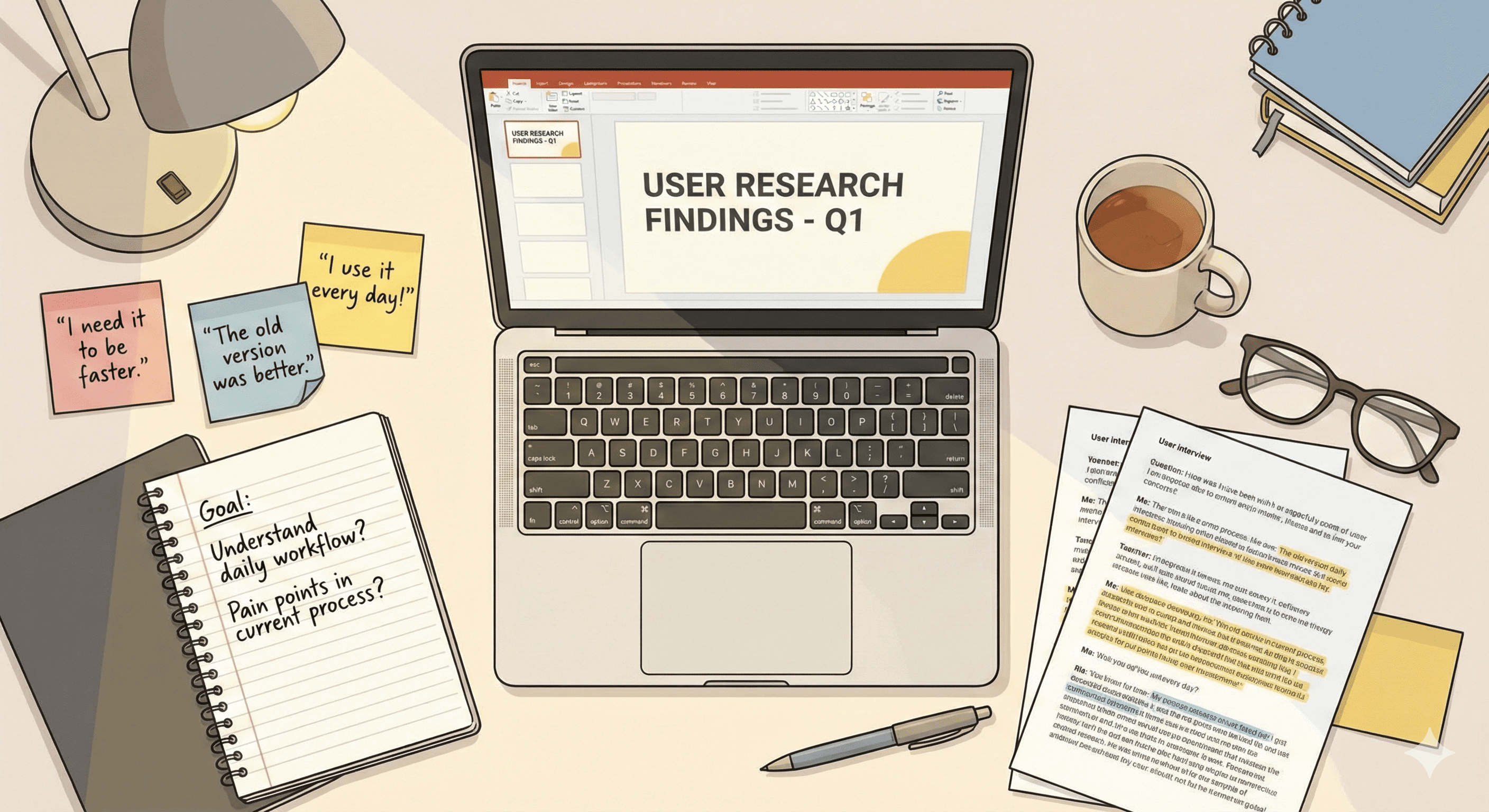

If you’ve ever wondered “how do I analyze my user interviews?” or “what do I do with all these transcriptions?”, this article is for you. Thematic analysis is the perfect starting point for learning qualitative analysis in UX Research.

What is thematic analysis?

Thematic analysis is a method for identifying patterns (themes) across qualitative data. It’s not just “reading interviews and drawing conclusions” — it’s a systematic and rigorous process that gives credibility to your findings.

Imagine you have 15 interviews with users of a banking app. Thematic analysis allows you to:

- ✅ Find repeated behavior patterns

- ✅ Identify common usability problems

- ✅ Discover needs not explicitly expressed

- ✅ Justify design decisions with solid evidence

Why is thematic analysis ideal for beginners?

According to Lester, Cho, and Lochmiller (2020), thematic analysis offers three key advantages:

- Theoretical flexibility: You can use it with any approach (UX, CX, Service Design, etc.)

- Common practices: Uses techniques you’ll find in other qualitative methods

- Wide applicability: Works with interviews, observations, open surveys, etc.

When to use thematic analysis?

✅ Use it when you need to:

- Analyze discovery interviews with users

- Interpret usability test observations

- Understand open-ended survey responses

- Identify patterns in user diaries

- Analyze qualitative stakeholder feedback

❌ Maybe it’s not ideal if:

- You only have 2-3 interviews (too little)

- You need detailed conversational analysis (better: Discourse Analysis)

- Your research question is very specific and you already have a theory to test (better: directed Content Analysis)

The 7 phases of thematic analysis

Based on Lochmiller and Lester’s (2017) framework, here are the 7 phases you should follow:

Phase 1: Prepare and organize the data

What do you do?

- Gather all audio/video files in one folder

- Create consistent naming (e.g.,

P01_discovery_2025-02-10.mp3) - Generate a master data catalog with:

- Data source

- File location

- Collection date

- Participant/role

Practical tip:

Discovery_Interviews/

├── P01_banking_app_user_2025-02-05.mp3

├── P02_banking_app_user_2025-02-06.mp3

├── ...

└── data_catalog.xlsx (name, role, date, duration, notes)

Recommended tools:

- NVivo, ATLAS.ti, or MAXQDA to import data

- Google Drive or Dropbox to organize files

- Excel/Notion for the master catalog

Phase 2: Transcribe the data

Types of transcription:

| Type | What it includes | When to use it |

|---|---|---|

| Verbatim | Every word, pause, laugh, filler | Deep thematic analysis |

| Intelligent | Exact words, no fillers | Most UX analyses |

| Summarized | Key ideas, not literal | Only for initial exploration |

Transcribe yourself or outsource?

Advantages of transcribing yourself:

- Deep familiarity with the data

- Detect insights while transcribing

- Speeds up later analysis

Practical reality:

- 1 hour of audio = 4-6 hours of manual transcription

- Automatic transcription tools (Otter.ai, Trint, Temi) reduce this to 1 hour of review

My recommendation: Use automatic transcription + manual review. You get the best of both worlds.

Phase 3: Become familiar with the data

Key activities:

- Read all transcripts without coding (just reading)

- Listen to audio while reading to capture emotion and emphasis

- Note first impressions in the margins:

- “Everyone mentions frustration with payment flow!”

- “Pattern: users >50 years prefer calling the bank”

- “Gap: nobody talked about push notifications”

Recommended time: 30-60 minutes per 1-hour interview.

Real example:

If you’re analyzing usability tests of a health app, you might note:

- “P03 confused 3 times with ‘Save’ vs ‘Submit’ button”

- “P07 expected SMS code confirmation”

- “Emerging pattern: users don’t trust saving medical data without visual confirmation”

Phase 4: Memoing (conversation with yourself about the data)

What is a memo?

A memo is an analytical note where you reflect on:

- Emerging interpretations

- Connections between participants

- Your possible biases

- Questions to investigate further

Memo example:

## Memo: Trust in Medical Data (2025-02-13)

**Observation:** 8 of 12 participants expressed distrust when saving

medical data in the app without explicit confirmation.

**Initial interpretation:** This could be related to:

- Cultural norms about medical privacy in Chile

- Lack of visual feedback after "Save"

- Previous experiences with apps that "lose" data

**Question to investigate:** Is it the lack of visual confirmation,

or general distrust in technology?

**My possible bias:** I trust apps because I'm tech-savvy.

I must not project my trust onto users.

**Next step:** Review if users mention other apps

(banking, retail) with the same pattern.

Where to write memos:

- In your CAQDAS software (NVivo, ATLAS.ti) linked to data segments

- In a physical notebook (some researchers prefer this)

- In Notion/Obsidian as a knowledge base

Phase 5: Code the data (the heart of the analysis)

What is a code?

A code is a brief, descriptive label you assign to a data segment. Think of codes as “Instagram tags” for your data.

Example of coded segment:

Participant: “I tried to search for my doctor, but nothing came up. I searched by name, by specialty… nothing. In the end I called the call center and they scheduled it for me.”

Possible codes:

Failed searchFrustration with searcherWorkaround: call centerUsability problem

The 3 phases of coding

First pass: Descriptive coding (low level of inference)

- Assign codes to the ENTIRE dataset

- Use descriptive and literal codes

- Goal: Reduce data volume, mark what’s important

Example:

Mentions frustrationDidn't find the functionCompares with banking app

Second pass: Interpretive coding (medium level of inference)

- Review already coded segments

- Assign more conceptual codes

- Connect with your research questions

Example:

Unmet expectation(instead of “Didn’t find the function”)Mental model from other apps(instead of “Compares with banking app”)

Third pass: Theoretical coding (high level of inference)

- Connect codes with theoretical concepts or UX frameworks

- Link with heuristics, design principles, theories

Example:

Heuristic violation: Visibility of system status(Nielsen)Lack of affordance(Don Norman)Gap between mental model and system model

Practical coding tips

✅ Do:

- Start with 50-80 codes (you’ll group them later)

- Code the same phrase with multiple codes if applicable

- Review your codes every 2-3 interviews for consistency

- Maintain a codebook (glossary of codes with definitions)

❌ Avoid:

- Creating 300+ codes (too granular)

- One-word codes without context (

problem,good) - Only coding what “confirms” your hypothesis (confirmation bias)

Tool: Most CAQDAS (NVivo, ATLAS.ti, Dedoose) allow you to:

- Code text segments

- See code frequency

- Filter by participant, date, etc.

Phase 6: From codes → categories → themes

This is where you go from “many labels” to “actionable insights”.

What’s the difference?

| Level | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Code | Descriptive label | Failed search, Frustration, Called call center |

| Category | Group of related codes | Search problems (groups: failed search, filters don’t work, irrelevant results) |

| Theme | Significant pattern that answers your research question | Users resort to traditional channels when technology fails |

Grouping process

Step 1: Print all your codes (or put them on post-its)

- Failed search

- Filters don't work

- Irrelevant results

- Can't find doctor by name

- Search doesn't recognize accents

- Called call center

- Asked family for help

- Went to branch in person

Step 2: Group similar codes into categories

Category: "Search problems"

├─ Failed search

├─ Filters don't work

├─ Irrelevant results

├─ Can't find doctor by name

└─ Search doesn't recognize accents

Category: "Workarounds (alternative solutions)"

├─ Called call center

├─ Asked family for help

└─ Went to branch in person

Step 3: Identify the larger pattern (the theme)

Theme 1: “When technology fails, users return to traditional channels of trust”

This theme connects:

- Technical search problems (cause)

- Traditional workarounds (effect)

- Design implication: Improve search OR facilitate human contact

Theme validation:

A good theme should:

- ✅ Be evident in multiple participants (not just 1-2)

- ✅ Answer your research questions

- ✅ Be descriptive and specific (not vague)

- ✅ Be backed by evidence (verbatim quotes)

Bad theme: “Users have problems” (too vague)

Good theme: “Users abandon digital features when they require more than 2 attempts, preferring human contact as a safety net”

Cross-Cutting Phase: Reflexivity - Your Role as a Researcher

This phase is not linear — it occurs throughout the entire analysis process. It’s one of the most important quality markers in qualitative research (Stenfors et al., 2020).

Why does who you are matter?

A senior UX researcher analyzing user interviews will gain different insights than a junior designer analyzing the same interviews. Reflexivity is recognizing how your experience, biases, and context influence your analysis.

The same data can be interpreted differently depending on:

- Your role (Are you part of the internal team or an external consultant?)

- Your previous experience (Have you worked in fintech? In digital health?)

- Your age and cultural context

- Your prior hypotheses about the problem

Reflexivity questions you should ask yourself:

Before analysis:

- What relationship do I have with participants? (Am I part of the team? External?)

- What previous experience do I have with this type of product/service?

- What hypotheses do I have BEFORE reading the data? (Write them explicitly)

- What biases might I have? (age, gender, technical expertise, culture)

During analysis:

- Am I looking to confirm what the stakeholder wants to hear?

- Am I ignoring data that contradicts my prior beliefs?

- Is my technical/non-technical background influencing how I interpret “frustration”?

Example of reflexivity in action:

Reflexive memo:

## Reflexive Memo: "Workarounds" vs Legitimate Preferences (2025-02-13)

Today I noticed I'm coding all mentions of 'calling the bank' as 'workaround'

(alternative solution). But reflecting: Is it really a workaround or simply

the legitimate preference of users >60 years who trust human interaction more?

My bias: I (32 years old, digital designer) see any use of non-digital channels

as 'system failure'. I must reconsider whether for some users, calling is NOT a

workaround but their preferred channel.

Action: Review all codes related to "traditional channel" and re-evaluate

whether it reflects system failure or user preference.

How to document your reflexivity:

1. Declare your position in the final report:

Example:

“As a UX researcher with 5 years of experience in fintech and background in interaction design, I conducted interviews as an external consultant for [Company]. My familiarity with banking UX patterns may have influenced my sensitivity to usability problems, while my external position facilitated users expressing criticisms of the product.”

2. Reflexive memos during analysis (see Phase 4)

Write memos specifically about:

- Moments where you noticed a personal bias

- Interpretations where your experience influenced

- Data that surprised you (because it contradicted your expectations)

3. Validation with people of different profiles

- Present preliminary findings to someone without your background

- Ask them: “What do you interpret from this data?”

- If they see something different, explore why

Why this matters in UX Research:

- Your stakeholders will trust transparent findings more

- Recognizing biases makes you a better researcher, not worse

- Qualitative research is co-construction between you and the data (not “objective truth”)

- Improves credibility of your findings (Stenfors et al., 2020)

Practical tool: Maintain a “Reflexivity Journal”

Date | Reflexive observation | Action taken

-----|----------------------|-------------

2025-02-10 | Noticed I'm ignoring positive mentions of the search | Review data and also code aspects that work well

2025-02-12 | My e-commerce background makes me assume "add to favorites" is intuitive | Validate if for users >60 this concept is clear

Phase 7: Transparency and traceability of the analysis

Why does it matter?

When you present findings to stakeholders or publish a case study, they need to trust that your analysis was rigorous, not just “opinions”.

3 transparency strategies

1. Analysis map (Audit Trail)

Create a table showing the path from data → theme:

| Verbatim quote (evidence) | Initial code | Category | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| “I searched 10 minutes and nothing… I called the call center” | Failed search → Call center workaround |

Search problems / Workarounds | Return to traditional channels |

| “My son helped me schedule, I couldn’t alone” | Asked family for help |

Workarounds | Return to traditional channels |

2. Visual process map

Document your analysis process:

15 interviews

↓

[Phase 1-3] Prepare, transcribe, familiarize

↓

[Phase 4-5] Memoing + Coding (3 passes)

↓

157 initial codes

↓

Grouped into 23 categories

↓

5 final themes

3. Frequency report (optional, depends on your audience)

Some stakeholders value quantifying:

- “Theme 1: Return to traditional channels (mentioned by 11 of 15 participants)”

- “Code ‘Frustration with search’: 47 mentions throughout the dataset”

Tool: NVivo, ATLAS.ti, and MAXQDA automatically generate frequency reports.

Documenting Context for Transferability

Why does context matter?

A finding about “users who prefer traditional channels” may be valid in your study of a Chilean banking app for users >50 years old, but NOT transferable to a study of a delivery app for millennials in Mexico.

“Findings may inform theory and methodology development, but they may not be directly transferable to other social or organizational settings.” — Stenfors et al. (2020)

Transferability is NOT statistical generalization. In qualitative research, the goal is for other researchers to evaluate whether your findings apply to their context, but for that they need to know YOUR context in detail.

Contextual information you should ALWAYS document:

1. Participant context:

## Participant Profile

**Demographics:**

- Age: 55-70 years (average: 62)

- Gender: 8 women, 7 men

- Education: 60% higher education, 40% complete secondary

- Occupation: 11 retired, 4 employed

**Digital literacy:**

- Basic level: 40% (use WhatsApp and email)

- Intermediate level: 53% (use basic banking apps)

- Advanced level: 7% (use multiple fintech apps)

**Previous experience:**

- All traditional bank users for 15+ years

- 80% occasionally use online banking

- 20% never used digital banking before

**Location:** Metropolitan Region, Chile (urban context)

**Cultural context:** Chilean users with high financial risk aversion

2. Product context:

## Studied Product Characteristics

**Industry:** Retail banking (savings and investment products)

**Product type:** iOS/Android mobile app

**Maturity:** Established product (3 years in market)

**Competition:** Market with 5 traditional banks + 3 fintechs

**Regulation:** Subject to CMF regulation (Financial Market Commission)

3. Study context:

## Study Conditions

**Period:** January-February 2025 (summer, post-holidays)

**Recruitment method:**

- 60% current bank customers (invited by email)

- 40% UX research panel (incentivized)

**Incentive:** $30,000 CLP gift card (may attract money-motivated participants)

**Modality:** Remote interviews via Zoom (60-90 min)

**Interviewer:** External UX researcher (not bank employee)

**Relevant temporal context:**

- Post-2019 social crisis (high distrust in institutions)

- During post-COVID normalization (users returning to branches)

Transferability statement (example):

At the end of your findings report, include:

Transferability of findings:

These findings are based on 15 interviews with Chilean users aged 55-70, with basic-intermediate digital literacy, current users of a traditional banking app in urban context.

The identified patterns about ‘return to traditional channels when technology fails’ are probably transferable to:

- ✅ Other digital banking contexts for older adults in Latin America

- ✅ High perceived-risk financial services (investments, loans)

- ✅ Users with low trust in digital institutions

These findings are probably NOT transferable to:

- ❌ Digital native users (18-35 years)

- ❌ Lower perceived-risk industries (delivery apps, entertainment)

- ❌ Contexts where physical branches don’t exist (100% digital banks)

- ❌ Countries with high fintech penetration (e.g., Brazil, urban Mexico)

Contextual documentation template:

Use this structure when writing your research report:

# Study Context

## 1. Objective and Research Question

[What did you want to answer?]

## 2. Participants

- Inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Demographics

- Relevant experience level

- Recruitment method

## 3. Product/Service Studied

- Industry and category

- Product maturity

- Competitive context

## 4. Collection Method

- Technique (interviews, observation, etc.)

- Duration and modality

- Collection period

- Who conducted collection

## 5. Temporal and Cultural Context

- Relevant events of the period

- Sociocultural context influencing findings

## 6. Known Limitations

[E.g., "Only urban users, not rural"]

## 7. Estimated Transferability

[Where findings DO and DON'T apply]

Why this matters for UX Research:

- Your stakeholders can evaluate whether to apply findings to other products

- Other research teams can replicate your study in their context

- You prevent findings from being incorrectly generalized

Ensuring quality in your thematic analysis

Stenfors, Kajamaa, and Bennett (2020) propose specific quality criteria for qualitative research. Here I adapt them for UX Research:

The 5 criteria of trustworthiness (reliability)

According to Stenfors et al. (2020), these are the criteria that define quality in qualitative research:

| Criterion | What it means | How to recognize it in your analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility | Findings are plausible and trustworthy | There’s alignment between theory, research question, data collection, analysis, and results. Sampling strategy, data depth, and analytical steps are appropriate |

| Dependability | The study could be replicated under similar conditions | You documented enough information for another researcher to follow the same steps (though possibly reaching different conclusions) |

| Confirmability | There’s a clear link between data and findings | You show how you arrived at your findings through detailed descriptions and use of verbatim quotes |

| Transferability | Findings can be applied to another context | Detailed description of the context in which research was conducted and how this shaped the findings |

| Reflexivity | Continuous process of articulating the researcher’s place | Explanations of how reflexivity was embedded and documented during the research process |

When to stop interviewing? Information Power vs Saturation

The saturation myth:

Many researchers say: “I stop when no new codes emerge” (theoretical saturation). Problem: This concept is problematic, misunderstood, and can be counterproductive (Varpio et al., 2017).

Why is “saturation” problematic?

- Implies there’s a “complete truth” to discover

- Doesn’t consider that new codes can ALWAYS emerge with more data

- Can be used as an excuse to stop collecting data prematurely

Better concept: Information Power (Malterud et al., 2016; Varpio et al., 2017)

Your sample has sufficient information power when your data allow for:

- Answering your research question with confidence

- Transferability to similar contexts (with adequate context description)

- Methodological alignment with your approach (narrow study = less data; broad study = more data)

Factors determining how many participants you need:

| Factor | Fewer participants OK | More participants needed |

|---|---|---|

| Study scope | Narrow (e.g., “specific payment flow”) | Broad (e.g., “complete service experience”) |

| Sample specificity | Very specific (e.g., “cardiologists >50 years”) | General (e.g., “digital health users”) |

| Use of theory | Study based on solid existing theory | Exploratory study without prior theory |

| Dialogue quality | Deep 90-min interviews with high information | Superficial 20-min interviews |

| Analysis strategy | Thematic analysis (flexible) | Grounded theory (requires more data) |

Practical example:

Study A: “Why do users 60+ abandon the payment flow in our specific banking app?”

- Scope: Narrow (only a specific flow)

- Sample: Specific (60+, banking app, Chile)

- Theory: Based on usability heuristics (Nielsen)

- Quality: Deep interviews with screen sharing

- Participants needed: 8-12

Study B: “How do low-income people manage their finances digitally?”

- Scope: Broad (all digital finances: banks, wallets, loans)

- Sample: General but diverse (different apps, banks, contexts)

- Theory: Exploratory (no prior framework)

- Quality: Contextual field interviews

- Participants needed: 25-40

How to know if you have sufficient information power:

Instead of looking for “saturation,” ask yourself:

Information power checklist:

- [ ] Can I answer my research question with this data?

- [ ] Do I have sufficient evidence (quotes from multiple participants) to support each theme?

- [ ] Did I interview different “types” of users relevant to my context? (e.g., novices and experts, young and old)

- [ ] Can stakeholders make design decisions with this information?

- [ ] Did I document enough context for others to evaluate transferability?

- [ ] Do themes answer questions that matter to the business/product?

✅ Yes to all 6 questions → You have sufficient information power

Practical tip: Instead of deciding “we’ll do 15 interviews,” propose:

- “We’ll do between 10-20 interviews, evaluating information power every 5 interviews”

- This allows flexibility based on data richness, not arbitrary number

Participant Validation (Member Reflections)

What is it?

Presenting your preliminary findings to some original participants to (Stenfors et al., 2020):

- Verify that your interpretation resonates with their experience

- Elaborate or deepen emergent themes

- Identify misinterpretations

Is it mandatory? No. It’s an OPTIONAL strategy that can improve analysis credibility.

How to do it:

Step 1: Select 3-5 participants representative of different “types” in your sample

Step 2: Prepare preliminary findings (1 page, simple language, no academic jargon)

Step 3: Send by email or schedule 30-min session

Step 4: Ask:

- “Do these findings resonate with your experience?”

- “Is there anything missing or misinterpreted?”

- “Can you elaborate more on [specific theme]?”

Example email for member reflection:

Subject: Findings validation - Banking App UX Study

Hi [Name],

Thank you again for participating in our research on [topic]. We've completed

preliminary analysis and I'd like to validate our findings with you.

**Key finding identified:**

Users like you resort to traditional channels (call center, branch) when the

digital search fails more than 2 times, prioritizing efficiency over

digitalization. This especially happens in high perceived-risk tasks like

scheduling medical appointments or large transfers.

**Questions:**

1. Does this interpretation reflect your experience?

2. Are there nuances we should consider?

3. What else would you add about this pattern?

I'd appreciate 15 minutes of your time to discuss this briefly.

I can call you or do a short video call.

Thanks,

[Your name]

When NOT to use member reflections:

- ❌ When participants are stakeholders with agendas (may bias toward findings favoring their interests)

- ❌ When analysis is critical/sensitive (e.g., negative findings about participant’s company)

- ❌ When study is ethnographic and participants aren’t aware of their own cultural patterns

- ❌ When you have severe time/budget constraints

Alternative to member reflections: Validation with other researchers or diverse stakeholders (perspective triangulation)

Quality checklist (Braun & Clarke, 2006)

Use this checklist before presenting findings:

Transcription:

- [ ] Transcriptions are accurate and represent original data

- [ ] I reviewed transcriptions vs audio at least once

Coding:

- [ ] Each relevant data segment was coded

- [ ] Codes are consistent throughout the dataset

- [ ] I didn’t force data to “confirm” my prior hypothesis

- [ ] I coded the entire dataset, not just “interesting” parts

Themes:

- [ ] Themes are coherent patterns, not just grouped codes

- [ ] There’s sufficient evidence (quotes) for each theme

- [ ] Themes answer my research question

- [ ] I didn’t confuse “themes” with “my interview script questions”

Report:

- [ ] The report balances analytical description with illustrative quotes

- [ ] I documented my analysis process (audit trail)

- [ ] Interpretations are grounded in data

- [ ] I was transparent about analysis limitations

Academically Recognized Quality Frameworks

When presenting findings to academic stakeholders, research ops, or for publication, they might ask: “Did you follow COREQ/SRQR?”

These are standardized frameworks for reporting qualitative research with academic rigor.

COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research)

32 items organized into 3 domains (Tong et al., 2007):

1. Research team & reflexivity (8 items)

- Who conducted interviews? (credentials, gender, experience, training)

- What relationship did they have with participants? (insider vs outsider)

- What motivated the study? (interests, personal/professional reasons)

2. Study design (15 items)

- Theoretical framework guiding the study

- Participant selection (criteria, contact method, sample size)

- Setting (where interviews were conducted: in-person, remote, specific location)

- Presence of non-participants during interviews

- Interview guide description (pilot questions, versions)

- Repeat interviews (if done and why)

- Audio/video recording

- Field notes (who took them, when)

- Duration of interviews

- Data saturation (or information power)

- Transcriptions (who did them, participant validation)

3. Analysis & findings (9 items)

- Number of coders and characteristics

- Coding tree description (codebook)

- Theme derivation (grouping process)

- Software used (NVivo, ATLAS.ti, manual)

- Participant checking (member reflections)

- Quotes presented (participant identification)

- Consistency between data and findings

- Clarity between major and minor findings

- Complete results reporting

When to use COREQ:

- ✅ Academic publications

- ✅ Reports for ethics committees

- ✅ Studies to be used as scientific evidence

- ✅ High-rigor research ops

Download complete checklist: COREQ 32-item checklist

SRQR (Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research)

21 items for qualitative research reports (O’Brien et al., 2014)

Similar to COREQ but more focused on medical education, health, and UX research.

Main categories:

- Title and abstract

- Introduction (problem, purpose, question)

- Methods (paradigm, researcher characteristics, context, sampling, ethical data, data collection, processing, analysis)

- Results (synthesis, interpretation)

- Discussion (links to literature, transferability)

- Other (funding, conflicts of interest)

When to use SRQR:

- ✅ Digital health research

- ✅ User behavior studies

- ✅ Research ops in regulated companies

Download complete checklist: SRQR Guidelines

CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)

10 questions to evaluate qualitative studies:

- Is there a clear statement of research aims?

- Is qualitative methodology appropriate?

- Is the research design appropriate for addressing aims?

- Is the recruitment strategy appropriate?

- Was data collected appropriately?

- Was the researcher-participant relationship adequately considered?

- Were ethical issues considered?

- Was data analysis rigorous?

- Is there a clear statement of findings?

- How valuable is the research?

When to use CASP:

- ✅ To self-evaluate your study before presenting

- ✅ To review others’ studies as benchmark

- ✅ To teach qualitative research quality

Download: CASP Qualitative Checklist

Which framework to use?

For internal corporate UX projects:

- Braun & Clarke (2006) checklist is sufficient ✅

- Add trustworthiness criteria (Stenfors et al., 2020)

For research ops or high-rigor studies:

- Use COREQ (interviews/focus groups) or SRQR (any qualitative method)

- Document during the study, not at the end

For academic or scientific publications:

- Journals will explicitly require COREQ or SRQR

- Some journals have their own guidelines (check author guidelines)

Practical tip:

Download the relevant checklist BEFORE starting your study. Use it as a guide to document during research, not as a post-hoc checklist.

Example: If you know you’ll need COREQ, document from day 1:

- Who conducted interviews

- Exact duration of each interview

- Field notes

- Transcription process

- Etc.

It’s easier to document in real-time than reconstruct months later.

Common mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Mistake 1: Confusing themes with question summaries

❌ Bad theme: “What users said about the search”

✅ Good theme: “The current search doesn’t meet the simple search mental model users bring from Google and banking apps”

Solution: Themes should be interpretations, not descriptions.

Mistake 2: Themes based on frequency alone

❌ Bad reasoning: “This code appeared 50 times, so it’s a theme”

✅ Good reasoning: “This pattern is relevant because it answers our key question about why users abandon the flow”

Solution: Relevance > frequency.

Mistake 3: Confirmation bias

❌ Bias: I only code what confirms that “the search is bad” (my prior hypothesis)

✅ Rigor: I code EVERYTHING, including cases where the search worked well or where the problem was something else

Solution: Actively seek evidence that contradicts your hypotheses.

Mistake 4: Superficial analysis

❌ Superficial: “Theme 1: Usability problems. Theme 2: Improvement suggestions.”

✅ Deep: “Users interpret lack of results as system failure, not actual data absence, which generates distrust in the entire app”

Solution: Ask “So what?” until you reach actionable insights.

Complete example: From transcription to theme

Raw data (transcription)

Interviewer: How was your experience searching for a doctor in the app?

P08: Ugh, frustrating. I searched “cardiologist” and got like 20, but none in my neighborhood. There was no way to filter by location. I tried typing “cardiologist Las Condes” but it didn’t work. In the end I called the call center and they scheduled me in 2 minutes. The traditional way was faster.

Coding (3 passes)

First pass (descriptive):

FrustrationSearch by specialtyGeographically irrelevant resultsLocation filter not availableNatural language search failedCalled call centerCall center was faster

Second pass (interpretive):

Geographic filter expectation not metGoogle-type search mental model (natural language)Workaround: traditional channelEfficiency comparison: digital < human

Third pass (theoretical):

Gap between mental model (Google) and system modelHeuristic violation: Flexibility and efficiency of use (Nielsen #7)

Categorization

Category 1: Search problems

- Geographically irrelevant results

- Location filter not available

- Natural language search failed

Category 2: Workarounds

- Called call center

- Call center was faster

Emerging theme

Theme: “Users expect intelligent search capabilities (Google-like) that the current app doesn’t offer, leading them to prefer traditional human channels that solve their need in fewer steps.”

Design implication:

- Add geographic location filter in search

- Or implement natural language search (“cardiologist in Las Condes”)

- Or highlight “Talk to an advisor” option as a legitimate alternative

Recommended tools

CAQDAS Software (Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis)

| Tool | Price | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVivo | $1,500 USD (cheaper academic license) | Very complete, research standard | Steep learning curve |

| ATLAS.ti | $99-700 USD/year | More intuitive interface | Fewer features than NVivo |

| MAXQDA | €1,500 (perpetual license) | Excellent for teams | Expensive for freelancers |

| Dedoose | $15/month | Web-based, collaborative | Requires internet always |

| Delve | Free (basic) | Free, easy to use | Limited features |

My recommendation to start: Dedoose or Delve (low cost). If your organization pays, NVivo or ATLAS.ti.

Low-tech alternatives

- Excel/Google Sheets: Works for small projects (5-10 interviews)

- Notion: With a well-structured database, you can code manually

- Paper and post-its: Surprisingly effective for 3-5 interview projects

Estimated time per phase

For a typical project of 12 60-minute interviews:

| Phase | Estimated time |

|---|---|

| 1. Prepare and organize | 2-3 hours |

| 2. Transcribe (with automatic tool + review) | 15-20 hours |

| 3. Familiarization | 6-12 hours |

| 4. Memoing (continuous during coding) | 5-8 hours |

| 5. Coding (3 passes) | 25-35 hours |

| 6. Categorization and themes | 8-12 hours |

| 7. Document process | 4-6 hours |

| TOTAL | 65-96 hours (~2-2.5 weeks full-time) |

Tip: Don’t underestimate analysis time. As a general rule: 1 hour of interview = 6-8 hours of complete analysis.

Additional resources to go deeper

Essential readings

-

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). “Using thematic analysis in psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

- The foundational paper on modern thematic analysis. Must-read.

-

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). “Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners.”

- Complete book, very didactic, with step-by-step examples.

-

Saldaña, J. (2016). “The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers.”

- Definitive reference on coding. 30+ coding methods explained.

-

Lester, J. N., Cho, Y., & Lochmiller, C. R. (2020). “Learning to Do Qualitative Data Analysis: A Starting Point.”

- Article that inspired this blog post. Very practical for beginners.

Recommended courses

- Coursera: “Qualitative Research Methods” (University of Amsterdam)

- LinkedIn Learning: “Qualitative Research Design and Methods” by Erin Meyer

- UXPA: In-person workshops on qualitative analysis

Communities

- ResearchOps Community: Slack with channel dedicated to qualitative analysis

- UX Research Geeks: Facebook group with threads about coding

- Reddit r/userexperience: Subreddit with methods discussions

Conclusion: Your learning roadmap

Thematic analysis isn’t “reading interviews and drawing conclusions”. It’s a systematic, rigorous, and transparent process that requires practice.

Your action plan:

- Week 1: Read Braun & Clarke (2006). Familiarize yourself with the 7 phases.

- Week 2: Analyze 3 pilot interviews with this framework. It doesn’t matter if it’s not perfect.

- Week 3: Review your first analysis. Identify where you had difficulties.

- Week 4: Analyze a complete real project (10-15 interviews).

- Month 2+: Practice with different types of data (observations, open surveys, etc.).

Remember:

“There is no single right way to analyze qualitative data; it’s essential to find ways to use the data to think.” — Coffey & Atkinson (1996)

Thematic analysis is your foundation. Once you master it, you can explore more specialized methods (Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Framework Analysis). But this foundation will serve you forever.

Questions? Want to share your experience with thematic analysis? Leave me a comment or write to me directly.

Series: Mastering Qualitative Analysis

This article is part of a series on data analysis in UX Research:

- Complete Guide to Thematic Analysis (you are here)

- Coming soon: How to communicate qualitative findings to stakeholders

- Coming soon: Content analysis vs thematic analysis: when to use each?

If you found this article useful, you might also be interested in:

- How to choose the right UX Research methodology

- Complete User Journey Map guide

- Stakeholder interviews: guide and template

Bibliographic references:

- Anderson, V. (2017). Criteria for evaluating qualitative research. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 28(2), 125–133.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2016). (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(6), 739–743.

- Lester, J. N., Cho, Y., & Lochmiller, C. R. (2020). Learning to Do Qualitative Data Analysis: A Starting Point. Human Resource Development Review, 19(1), 94–106.

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760.

- O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17(6), 596–599.

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In C. Willig & W. S. Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (2nd ed., pp. 17–37). Sage.

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357.

- Varpio, L., Ajjawi, R., Monrouxe, L. V., O’Brien, B. C., & Rees, C. E. (2017). Shedding the cobra effect: Problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Medical Education, 51(1), 40–50.